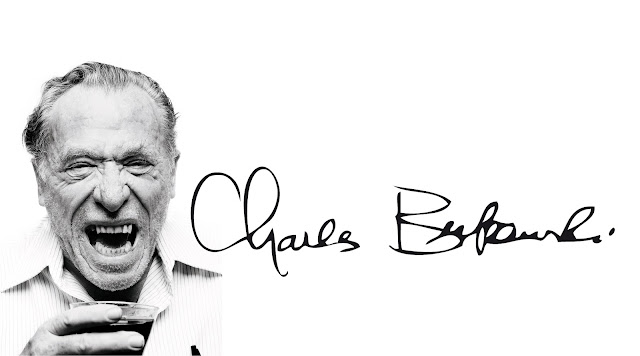

Lettera di Bukowski

» Lettera di Charles Bukowski al suo editore John Martin (Black Sparrow Press), 8 dicembre 1986:

Ciao John,

grazie per la bella lettera. Non credo faccia male, ogni tanto, ricordare da dove vieni. Tu sai da che posti sono venuto io. Perfino le persone che ne scrivono o ci fanno film non lo colgono per ciò che è. Lo chiamano "dalle 9 alle 5". Non è mai dalle 9 alle 5, non c'è la pausa pranzo in quei posti, infatti, in molti di essi per tenerti il posto di lavoro non pranzi. Poi c'è lo straordinario e i libri non sembrano mai rappresentarlo in modo corretto e se ti lamenti di questo c'è un altro coglione pronto a prendere il tuo posto.

Conosci il mio vecchio detto: «La schiavitù non è mai stata abolita, è stata solo estesa fino ad includere tutte le razze.»

E quello che fa male è la graduale e costante diminuzione di umanità in coloro che lottano per tenere il posto che non vogliono ma hanno troppa paura dell'alternativa peggiore. La gente semplicemente si svuota. Sono corpi con menti paurose ed obbedienti. Il colore abbandona i loro occhi. La voce diventa sgradevole. E anche il corpo, i capelli, le unghie, le scarpe. Tutto diventa sgradevole.

Da giovane non potevo credere che la gente potesse vendersi a quelle condizioni. Da vecchio ancora non riesco a crederci. Per che cosa lo fanno? Sesso? TV? Un'automobile a rate? Figli? Figli che faranno solo la stessa vita loro?

Tempo fa, quand'ero abbastanza giovane e passavo da un posto di lavoro all'altro ero abbastanza stupido da parlare qualche volta ai miei colleghi: «Hey, il capo può venire qui in ogni momento e metterci tutti per strada, così di punto in bianco; non ve ne rendete conto?».

Mi guardavano e basta. Gli mettevo davanti qualcosa che non volevano entrasse nelle loro menti.

Oggi nell'industria ci sono grandi licenziamenti (acciaierie morte, cambiamenti tecnici in altri aspetti del lavoro). Vengono licenziati a migliaia e le loro facce sono stupefatte:

«Ci avevo investito 35 anni...»

«Non è giusto...»

«Non so che cosa fare...»

Non pagano mai abbastanza gli schiavi perché si rendano liberi, solo quanto basta perché sopravvivano e tornino al lavoro il giorno dopo. Io lo vedevo chiaro. Perché loro no? Avevo capito che la panchina al parco era più o meno la stessa cosa, come essere un ubriacone. Perché non arrivarci prima che mi ci spedissero loro? Perché aspettare?

Scrivevo il disgusto di tutto questo, era un sollievo buttare la merda fuori dal mio organismo. E ora che sono qui, un cosiddetto scrittore professionista, dopo aver svenduto i primi 50 anni, ho scoperto che c'è altro disgusto al di là dell'organismo.

Mi ricordo una volta, mentre lavoravo come confezionatore in una compagnia di lampadari, uno dei confezionatori disse: «Non sarò mai libero!».

Uno dei capi passava di lì (si chiamava Morrie) e si lasciò andare in una deliziosa risata chioccia, divertito dal fatto che questo collega fosse intrappolato a vita.

Quindi, la fortuna di essere venuto fuori da questo tipo di posti, non importa quanto tempo ci sia voluto, mi ha dato una specie di gioia, la gioia festosa del miracolo. Oggi scrivo da una mente vecchia in un corpo vecchio, molto oltre l'età in cui molti uomini penserebbero di continuare a fare una cosa del genere, ma siccome sono partito così tardi devo a me stesso di continuare, e quando le parole cominciano ad inciampare e devo essere aiutato su per le scale e non riesco più a distinguere un pettirosso da una graffetta, sento ancora che dentro di me qualcosa si ricorderà (non importa quanto sono arrivato lontano) in che modo sono passato attraverso i crimini e la confusione e le difficoltà, per raggiungere almeno un modo generoso di morire.

Non aver sprecato l'intera vita sembra un risultato dignitoso, anche se solo a me.

Tuo,

Hank.

» Lettera originale:

Hello John:

Thanks for the good letter. I don’t think it hurts, sometimes, to remember where you came from. You know the places where I came from. Even the people who try to write about that or make films about it, they don’t get it right. They call it “9 to 5.” It’s never 9 to 5, there’s no free lunch break at those places, in fact, at many of them in order to keep your job you don’t take lunch. Then there’s overtime and the books never seem to get the overtime right and if you complain about that, there’s another sucker to take your place.

You know my old saying, “Slavery was never abolished, it was only extended to include all the colors.”

And what hurts is the steadily diminishing humanity of those fighting to hold jobs they don’t want but fear the alternative worse. People simply empty out. They are bodies with fearful and obedient minds. The color leaves the eye. The voice becomes ugly. And the body. The hair. The fingernails. The shoes. Everything does.

As a young man I could not believe that people could give their lives over to those conditions. As an old man, I still can’t believe it. What do they do it for? Sex? TV? An automobile on monthly payments? Or children? Children who are just going to do the same things that they did?

Early on, when I was quite young and going from job to job I was foolish enough to sometimes speak to my fellow workers: “Hey, the boss can come in here at any moment and lay all of us off, just like that, don’t you realize that?”

They would just look at me. I was posing something that they didn’t want to enter their minds.

Now in industry, there are vast layoffs (steel mills dead, technical changes in other factors of the work place). They are layed off by the hundreds of thousands and their faces are stunned:

“I put in 35 years…”

“It ain’t right…”

“I don’t know what to do…”

They never pay the slaves enough so they can get free, just enough so they can stay alive and come back to work. I could see all this. Why couldn’t they? I figured the park bench was just as good or being a barfly was just as good. Why not get there first before they put me there? Why wait?

I just wrote in disgust against it all, it was a relief to get the shit out of my system. And now that I’m here, a so-called professional writer, after giving the first 50 years away, I’ve found out that there are other disgusts beyond the system.

I remember once, working as a packer in this lighting fixture company, one of the packers suddenly said: “I’ll never be free!”

One of the bosses was walking by (his name was Morrie) and he let out this delicious cackle of a laugh, enjoying the fact that this fellow was trapped for life.

So, the luck I finally had in getting out of those places, no matter how long it took, has given me a kind of joy, the jolly joy of the miracle. I now write from an old mind and an old body, long beyond the time when most men would ever think of continuing such a thing, but since I started so late I owe it to myself to continue, and when the words begin to falter and I must be helped up stairways and I can no longer tell a bluebird from a paperclip, I still feel that something in me is going to remember (no matter how far I’m gone) how I’ve come through the murder and the mess and the moil, to at least a generous way to die.

To not to have entirely wasted one’s life seems to be a worthy accomplishment, if only for myself.

yr boy,

Hank